The simple answer to the question “What is X.400?” is that “it is a message transfer protocol – in principle very similar to e-mail, but over a dedicated network rather than the internet”.

Yes, although it is hard to imagine in this day and age, there are other networks that exist parallel to the Internet. In the B2B sector these networks are often called Value Added Networks (or VANs). Of these the X.400 network is probably the best known.

However, there is much more to X.400 than this, as we’ll explore in this article…

A quick review…

Before we go into the technical details, let’s turn back the clock a little: 30 years ago, in 1984, the Comité Consultatif International Téléphonique et Télégraphique (CCITT), now the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), first adopted X.400 as a standard. In 1988, the X.400 standard was extended. This distinction is still noticeable today, as some (sub)networks are still based on the old IPM84 (IPM stands for Interpersonal Messaging Standard, and 84 for the year 1984). Fortunately, however, these are largely compatible with the “newer” IPM88 networks.

The name IPM already indicates that X.400 should initially be positioned as a general mail or messaging system. At the same time, work on an e-mail system was already underway in the context of Internet protocols. The protocols SMTP, POP and IMAP – with the establishment of the Internet in our daily lives – then became established in the late 1990s as global standards for interpersonal messaging, i.e. e-mail. As we will see later, X.400 and Internet e-mail (i.e. SMTP/POP/IMAP) are relatively similar in their topology and mode of operation. However, X.400 is considered a much more complex protocol family, not least because of its additional functionalities.

While X.400 has been completely replaced by Internet e-mail in the interpersonal messaging sector, it has been able to secure a niche existence for the transmission of EDI messages. In Germany, access to the X.400 network is marketed by Deutsche Telekom under the name BusinessMail X.400 – formerly Telebox or Telebox400. Therefore the term Telebox is often still used today as a synonym for an X.400 mailbox. Besides AS2, X.400 is the most used protocol for the transmission of EDI messages today. While AS2 is not yet offered by every company for the transmission of EDI messages, the acceptance of X.400 for the exchange of EDI data can be described as very high.

Due to the not inconsiderable costs for the transmission of the messages – Deutsche Telekom still charges in kilobytes (!) – AS2 connections are increasingly in demand for medium to high message volumes. In order to save costs at low message volumes, it makes sense for SMEs and other supply chain organisations to enlist the help of an EDI provider. As providers purchase a higher volume of messages than individual supply chain businesses, they are able to achieve a better per-message cost. Suppliers can then pass these savings (as ecosio does) onto their customers. But this is a subject for another time. For now, let’s look further into the technical structure and functionality of X.400.

Structure of X.400 networks

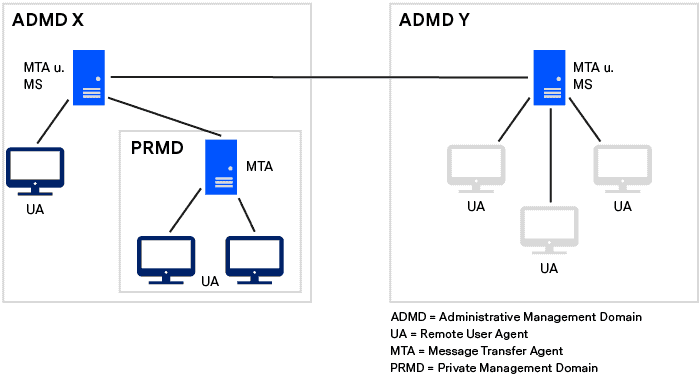

As with Internet e-mail, communication takes place via mailboxes. An X.400 mailbox is managed by a Message Store (MS) and identified by a unique address. Messages are transmitted to a mailbox via so-called Message Transfer Systems (MTS) or Message Transfer Agents (MTA) Users access their X.400 mailbox via User Agents – i.e. client software. The following figure provides a simplified overview of the topology of X.400 networks.

X.400 has a two-tier domain structure: An ADMD is a so-called public service area. ADMDs are usually operated by telecommunications companies – such as Deutsche Telekom. Several ADMDs can exist in a country. A PRMD is a so-called private utility area and is managed independently by companies for better organization. The distinction between ADMDs and PRMDs is an interesting technical detail – but in practice it hardly plays a role any more. Today, a company usually operates a single X.400 mailbox for the exchange of EDI messages or a few if it is a large company and there is a functional separation (e.g. ordering and invoicing processes).

Addressing in the X.400 network

Each X.400 mailbox is identified by a unique address – just like Internet e-mail. X.400 addresses are semantically structured similar to SMTP e-mail addresses, but are somewhat more complex in notation and often longer. Let’s look at the following example to explain the attributes of an address and how to read them:

G=Max; S=sample man; O=sample company; OU=purchasing; A=X400EXAMPLE; C=AT

This example address would identify the X.400 mailbox of Max Mustermann, who works in purchasing at Musterfirma. The mailbox would be hosted directly in the Austrian ADMD X400EXAMPLE – without using a PRMD. The attributes used in this example

C(Country name)ADMD(Administration Management Domain)O(Organisation name)OU(Organisational Unit Names)G(Given name)S(Surname)

are used very frequently in addresses. A more detailed overview of the use of addresses in networks is given in RFC 1685 or Harald T. Alvestrand’s X.400 Website (from 1995):

Deutsche Telekom also uses the attributes CN (Common Name) and n-id (User Agent Numeric ID) in its X.400 network (VIAT). Using these attributes can cause problems when addressing from/into an older IPM84 network (e.g. MARK400). The simplest workaround is to simply omit these attributes – the unique identification of the X.400 mailbox in the VIAT network can also be done without CN and n-id (if the parameters G and S are used).

Confirmation of message receipt

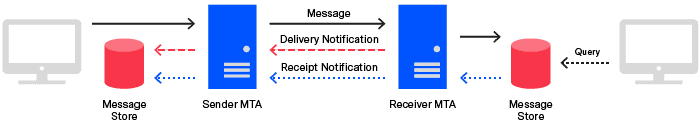

One feature – which is almost indispensable when transmitting EDI – is the notification of the sender that a message has been successfully received. X.400 knows two types of notifications.

Delivery Notification(DN): is generated by the server that places the message in the mailbox of the recipient and transmits to the sender MTA. This means the confirmation is generated by the server (on which the X.400 mailbox is hosted) and transmitted to the sender. The negative counterpart of the DN is the so-calledNon-delivery Notification(NDN) and is transmitted to the sender in case of an error.Receipt Notification(RN): can be generated by the recipient’s client software and is transmitted to the sender – in practice, the RN is hardly ever requested or supported in automated transmission. The negative counterpart of the RN is theNon-receipt notification(NRN).

The sequence is shown as an example in the following diagram.

Although in practice the Receipt Notification (RN) has hardly any significance, with the receipt of the Delivery Notification (DN) it can already be assumed that the EDI system of the recipient has received the message – at least on a technical level. The sender is then usually informed of any processing problems with the message via e-mail or telephone.

Importance of X.400 for EDI today

The end of X.400 message transmission has often been predicted – not least because of the high costs. But it is still impossible to imagine the EDI sector without it. In addition to the principle (particularly prominent in EDI) “never touch a running system”, the security aspects are a major advantage: After all, it is a separate network, physically separated from the Internet. Every participant is authenticated, which reduces the potential for abuse compared to SMTP/email to a minimum.

If you want to use an X.400 mailbox for your EDI data exchange or would like to reduce your existing X.400 costs, contact us today. We are always happy to answer any questions!